"Let her find a husband among the dead" (Sophocles, Antigone, 730)

It's been one heck of year in AP lit. In between the 4 novels, 3 plays, and gazillion pieces of poetry, this has been the most in depth I've ever gone with classical literature. I've always had a soft spot for a good book, so this course fit me to a tee. Throughout this course my love for challenging myself in reading was rejuvenated. After going through a phase of heavy reading in middle school, I sort of started slacking off. More genre fiction, less "hardcore literature". But now, I have a big pile of classics I'm planning on diving into over the summer.

The reason for this new enthusiasm was probably learning how to really read analytically and see hidden themes in literature. A poem like The Wasteland can seem like terribly dry, dull, and dross if readers don't know how to read deeply. But, with knowledge of literary techniques and an understanding of theme; the book becomes a darkly surreal reflection on the decline of western society, filled to the brim with brilliant and innovative techniques. That's a huge growth from my seventh grade perspective of "Wow, those are big word or something, this must be art!"

This past semester my favorite work was Antigone. I simply loved how catty and rude all the characters were, and the whole thing is packed with quotable lines. I also like how the Greek style combined theater with poetry. It was like, "Wow, that scene was crazy. I wonder what's going to happen next. Aw dude! Now here's some totally baller poetry! Aw man, that stuff's dope." Seriously, I never thought that I would find Greek tragedy so entertaining. If not for AP lit I probably never would have learned that about myself. So, thanks AP Literature and composition! It was fun knowing you...

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

Monday, May 2, 2016

Let's go team Edward!

Alright my blogging friends; let's talk about men! The novel Jane Eyre only contains a few guys, but they all play an important role in exposing the novel's theme through their characterization. Today we're going to be talking about Mr. Rochester and St. John Rivers (Jane's romantic interests).

First let's talk about Rochester. Throughout the book, Bronte characterizes Mr. Rochester as a man of passion and fire concerning all things. Take chapter 27 for instance. After Jane learns of Rochester's wife, she knows that she should leave Thornfield. But Rochester won't let her go without a fight. "Full of passionate emotion of some kind" (Bronte 349) Rochester tries to convince Jane to stay at Thornfield (to no avail). This scene makes it obvious that Rochester is a man who is absolutely desperately in love with Jane. Edward Rochester is holding nothing back in his love. Jane can see this, and she knows that their union would be a "paradise" from the "nightmare of parting" (Bronte 299). After the whole thing with Bertha however, Jane's logic takes over and tells her to leave behind her flaming-hot romance to find herself.

This is where St. John Rivers steps in. Although "Sinjin" gets substantially less screen time than Mr. Rochester, he is every bit as essential to Jane's development. John Rivers is a cold, logical man of God. This guy is seriously made out of ice. If I had a dollar for every time Bronte uses the word "cold" in reference to Rochester, I could probably buy lunch for the whole class. St. John is so passionless that "he was in reality become no more flesh, but marble" (Bronte 475). St. John and Jane's relationship would be a matter of pure business. Jane gets to do meaningful missionary work, and St. John gets to "have a wife". The marriage would be functional, but lack any sort of spark or romance. Just imagine the most "proper" marriage possible.

Mr. Rochester and St. John act as foils. Rochester represents the passion in Jane, and John Rivers symbolizes her desire to conform to Victorian ideals. By choosing to deny St. John and go back to Rochester, Jane chooses to seek her own desires rather than follow what society wants. This connects back to the novel's theme of Victorian women going in opposition to their conventional gender roles. Jane makes a choice; and that choice is to be free from her culture's expectations and live a life that pleases her. Society be darned!

First let's talk about Rochester. Throughout the book, Bronte characterizes Mr. Rochester as a man of passion and fire concerning all things. Take chapter 27 for instance. After Jane learns of Rochester's wife, she knows that she should leave Thornfield. But Rochester won't let her go without a fight. "Full of passionate emotion of some kind" (Bronte 349) Rochester tries to convince Jane to stay at Thornfield (to no avail). This scene makes it obvious that Rochester is a man who is absolutely desperately in love with Jane. Edward Rochester is holding nothing back in his love. Jane can see this, and she knows that their union would be a "paradise" from the "nightmare of parting" (Bronte 299). After the whole thing with Bertha however, Jane's logic takes over and tells her to leave behind her flaming-hot romance to find herself.

This is where St. John Rivers steps in. Although "Sinjin" gets substantially less screen time than Mr. Rochester, he is every bit as essential to Jane's development. John Rivers is a cold, logical man of God. This guy is seriously made out of ice. If I had a dollar for every time Bronte uses the word "cold" in reference to Rochester, I could probably buy lunch for the whole class. St. John is so passionless that "he was in reality become no more flesh, but marble" (Bronte 475). St. John and Jane's relationship would be a matter of pure business. Jane gets to do meaningful missionary work, and St. John gets to "have a wife". The marriage would be functional, but lack any sort of spark or romance. Just imagine the most "proper" marriage possible.

Mr. Rochester and St. John act as foils. Rochester represents the passion in Jane, and John Rivers symbolizes her desire to conform to Victorian ideals. By choosing to deny St. John and go back to Rochester, Jane chooses to seek her own desires rather than follow what society wants. This connects back to the novel's theme of Victorian women going in opposition to their conventional gender roles. Jane makes a choice; and that choice is to be free from her culture's expectations and live a life that pleases her. Society be darned!

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Being a Governess... It Just Works.

Jane Eyre challenges the structure of Victorian society by subverting many of its conventions through the use of Jane's job as a governess.

First off, the titular character is a governess in a very wealthy man's home. By making Jane a governess, Charlotte Bronte gives us an interesting perspective on class in Britain. Jane spends most of the novel very poor. Sure she has rich relations, but none of that wealth reaches her until chapter 30-something. As a governess, the Jane spends most of her time on a much richer man's estate. This allows Jane to comment on the lifestyle of the bourgeoisie from an outsiders perspective. It's much easier for Jane to critique the men and women partying at Thornfield because she wasn't born into a high position. She has no deep connection to the upper class and thus feels free to express her thoughts regarding them. I kind of like to pretend that Jane's some sort of crazy proto-marxist social commentator who speaks for all the poor through her interactions with the disconnected upper class. But maybe I'm reading into things a little too deeply...

Governesses are like wildcards in society due to their close proximity to powerful people. If Jane was just some seamstress in the streets of London she would never run into a man like Rochester. But in the confines of Thornfield, a servant like Jane grows close enough to her employer that he asks her to marry. This marriage is "improper" and tosses all of the Victorian era's rules about class on their head. Interactions like this give Governesses a huge amount more social mobility than anybody else really had at this time.

Where does Jane herself fit in to this whole mess? As a woman, Jane obviously had fewer freedoms than her male counterparts. But, Jane was an educated woman. This allowed her to land a job at Thornfield and have a shot at some upwards mobility. But, Jane was also poor. So who knows if she actually could have broken the cycle of poverty? BUT, Jane also had the power of the plot on her side. Bronte pulls out Huckleberry Finn levels of deus ex machina and reveals that Jane actually had a wealthy family the whole time. This (conveniently) gives Jayne an automatic new level of social standing almost equal to that of Rochester. Thus rendering the whole plot kind of pointless (in my opinion).

In conclusion, Jane Eyre uses the job of governess to portray Victorian class differences using a malleable perspective. But, does any of it really matter when Charlotte Bronte writes a happy fairy-tale ending that relegates all of the social commentary to secondary importance?

First off, the titular character is a governess in a very wealthy man's home. By making Jane a governess, Charlotte Bronte gives us an interesting perspective on class in Britain. Jane spends most of the novel very poor. Sure she has rich relations, but none of that wealth reaches her until chapter 30-something. As a governess, the Jane spends most of her time on a much richer man's estate. This allows Jane to comment on the lifestyle of the bourgeoisie from an outsiders perspective. It's much easier for Jane to critique the men and women partying at Thornfield because she wasn't born into a high position. She has no deep connection to the upper class and thus feels free to express her thoughts regarding them. I kind of like to pretend that Jane's some sort of crazy proto-marxist social commentator who speaks for all the poor through her interactions with the disconnected upper class. But maybe I'm reading into things a little too deeply...

Governesses are like wildcards in society due to their close proximity to powerful people. If Jane was just some seamstress in the streets of London she would never run into a man like Rochester. But in the confines of Thornfield, a servant like Jane grows close enough to her employer that he asks her to marry. This marriage is "improper" and tosses all of the Victorian era's rules about class on their head. Interactions like this give Governesses a huge amount more social mobility than anybody else really had at this time.

Where does Jane herself fit in to this whole mess? As a woman, Jane obviously had fewer freedoms than her male counterparts. But, Jane was an educated woman. This allowed her to land a job at Thornfield and have a shot at some upwards mobility. But, Jane was also poor. So who knows if she actually could have broken the cycle of poverty? BUT, Jane also had the power of the plot on her side. Bronte pulls out Huckleberry Finn levels of deus ex machina and reveals that Jane actually had a wealthy family the whole time. This (conveniently) gives Jayne an automatic new level of social standing almost equal to that of Rochester. Thus rendering the whole plot kind of pointless (in my opinion).

In conclusion, Jane Eyre uses the job of governess to portray Victorian class differences using a malleable perspective. But, does any of it really matter when Charlotte Bronte writes a happy fairy-tale ending that relegates all of the social commentary to secondary importance?

Monday, April 25, 2016

Parallel characters

In King Lear the characters of Lear and Gloucester seem to be parallels through act 3. Both of them share many similar trials and characteristics, but they each have some unique traits. In the last 2 acts however, I feel that the two become closer to being foils for each other.

Let's start with the similarities. First, (and most obviously) Lear and Gloucester are both old noblemen. The two characters being the same age helps establish and create similarities between them. Another similarity between the two men in this act is that both of them see a fall from grace. Lear loses all of his power to his daughters and Gloucester has title stripped by his bastard son--Edmund. This similarity is key because it feeds into the most essential parallel. Both men's falls from power are accompanied by some sort of physical or mental degradation. Gloucester loses his eyes, and Lear loses his mind.

It's here that we start to see the differences between Lear and Gloucester. For Lear, once he's gone crazy, he's out. He spends the rest of his time saying random things and prancing through fields (it's pretty weird). Gloucester on the other hand comes to term with his folly in trusting Edmund over Edgar. Lear dives headlong into flights of fancy while Gloucester sobers up to the harsh truth of betrayal. This critical difference makes the two characters into foils. While both had a similar path to their fall, the way they respond to it is hugely different.

Let's start with the similarities. First, (and most obviously) Lear and Gloucester are both old noblemen. The two characters being the same age helps establish and create similarities between them. Another similarity between the two men in this act is that both of them see a fall from grace. Lear loses all of his power to his daughters and Gloucester has title stripped by his bastard son--Edmund. This similarity is key because it feeds into the most essential parallel. Both men's falls from power are accompanied by some sort of physical or mental degradation. Gloucester loses his eyes, and Lear loses his mind.

It's here that we start to see the differences between Lear and Gloucester. For Lear, once he's gone crazy, he's out. He spends the rest of his time saying random things and prancing through fields (it's pretty weird). Gloucester on the other hand comes to term with his folly in trusting Edmund over Edgar. Lear dives headlong into flights of fancy while Gloucester sobers up to the harsh truth of betrayal. This critical difference makes the two characters into foils. While both had a similar path to their fall, the way they respond to it is hugely different.

Wednesday, April 13, 2016

Yay For Intertextuality!

Do you know what's cool? Paintings. You know what else is cool? Poetry. BUT, do you know what the coolest thing ever is? Poems that tie-in with paintings. Just throw in some connections to Shakespeare's King Lear and you've got the most awesome AP Lit assignment ever! Let's dive in, shall we?

Let's start with the pretty painting! This picture by renaissance master Pieter Bruegel is titled Landscape With the Fall of Icarus. This painting presents a fairly idyllic scene of ancient Greece. There's farmers farming, ships sailing, and a lovely town in the background. Among all of this however, there is an odd detail in the lower right corner. A pair of legs (belonging to Icarus) are sticking out from the sea.

But why are the legs so small and unimportant? Isn't this supposed to be a painting about the fall of Icarus?

Pieter Bruegel was a master of the style known as "world landscape". This technique takes famous historical or mythological events and put them into a larger context. The background dwarfs "the scene" in order to convey how small and unimportant the events occurring truly are. World Landscapes give viewers a sense of perspective on how little the world cares about any one person's struggles. So, while the title is Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, the painting isn't really about the guy's tragedy.

Due to the whole "great suffering going unnoticed by the world/society" thing, poets absolutely love this painting. William Carlos Williams and W. H. Auden have both given the painting treatments in verse, but they each take a slightly different angle on how the world sees suffering. William's poem Landscape With the Fall of Icarus focuses on the farmers in the foreground and their ignorance of Icarus' plight. The poem refers to Icarus hitting the water as "a splash quite unnoticed" by the farmers plowing their fields. It's not that the farmers (and the world) knowingly ignore the drowning boy so much as they never even knew that he fell. This contrasts directly with Auden's view in his poem Musee des Beaux Arts. Auden's treatment of the painting focuses on the ship sailing next to Icarus. Auden talks about how the ships willingly turn away from the tragedy and keep on sailing. This shows that Auden feels that people know of other's suffering, but choose to ignore it.

How does this all connect to King Lear? Well, the largest parallel I see is in Goneril and Regan, Lear's daughters. Both of these women know that father has grown old and isn't in the best of shape. Yet, when he simply seeks a place to live, they shun him and plot to eliminate him. These characters are obviously like Auden's interpretation of the ship that turns and sails away from suffering. This arguably makes them much more malicious than a character who is merely ignorant of Lear's suffering.

The connections between these texts give us a deeper understanding of the themes of each work. The painting gives visual to the poems and the poems give focus to the painting. All of these show readers a theme in king Lear that lies slightly below the surface of the text. It's like, magic...

Let's start with the pretty painting! This picture by renaissance master Pieter Bruegel is titled Landscape With the Fall of Icarus. This painting presents a fairly idyllic scene of ancient Greece. There's farmers farming, ships sailing, and a lovely town in the background. Among all of this however, there is an odd detail in the lower right corner. A pair of legs (belonging to Icarus) are sticking out from the sea.

But why are the legs so small and unimportant? Isn't this supposed to be a painting about the fall of Icarus?

Pieter Bruegel was a master of the style known as "world landscape". This technique takes famous historical or mythological events and put them into a larger context. The background dwarfs "the scene" in order to convey how small and unimportant the events occurring truly are. World Landscapes give viewers a sense of perspective on how little the world cares about any one person's struggles. So, while the title is Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, the painting isn't really about the guy's tragedy.

Due to the whole "great suffering going unnoticed by the world/society" thing, poets absolutely love this painting. William Carlos Williams and W. H. Auden have both given the painting treatments in verse, but they each take a slightly different angle on how the world sees suffering. William's poem Landscape With the Fall of Icarus focuses on the farmers in the foreground and their ignorance of Icarus' plight. The poem refers to Icarus hitting the water as "a splash quite unnoticed" by the farmers plowing their fields. It's not that the farmers (and the world) knowingly ignore the drowning boy so much as they never even knew that he fell. This contrasts directly with Auden's view in his poem Musee des Beaux Arts. Auden's treatment of the painting focuses on the ship sailing next to Icarus. Auden talks about how the ships willingly turn away from the tragedy and keep on sailing. This shows that Auden feels that people know of other's suffering, but choose to ignore it.

How does this all connect to King Lear? Well, the largest parallel I see is in Goneril and Regan, Lear's daughters. Both of these women know that father has grown old and isn't in the best of shape. Yet, when he simply seeks a place to live, they shun him and plot to eliminate him. These characters are obviously like Auden's interpretation of the ship that turns and sails away from suffering. This arguably makes them much more malicious than a character who is merely ignorant of Lear's suffering.

The connections between these texts give us a deeper understanding of the themes of each work. The painting gives visual to the poems and the poems give focus to the painting. All of these show readers a theme in king Lear that lies slightly below the surface of the text. It's like, magic...

Wednesday, April 6, 2016

The old man and the large rainstorm

Many of Shakespeare's plays contain scenes that could be considered "Iconic". Macbeth has the witch scene, Hamlet talks to skull, and Romeo proclaims sweet nothings at a balcony. Those are just from the top of my head! The play King Lear has its iconic moment in act 3 scene 2 when a deranged King Lear and his fool journey out into a storm and things start to get slightly... Cray. The king is rambling on about the most random things and the fool is all like "dude, let's get inside". This carries on until Kent enters and leads the king to hovel.

This scene has been immortalized in art as an essential part of Shakespeare's canon. But why? Why would the image of an insane old man wandering in a storm become so popular? How does it still resonate with readers after 400 years?

I feel that the answer is twofold. First, the scene presents the character of Lear at his most miserable. The whole scene starts with Lear crying out to the sky "blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow" (Shakespeare III, ii). Right from the beginning the audience knows that Lear is feeling agitated. Lear carries on like this for the whole scene. He cries to the skies and moans of his wicked daughters. Through all of this the audience sees lear's sanity unfold before them and the king even admits "my wits begin to turn" (Shakespeare III, ii). Through all of this the audience gets a deep look into Lear's descent to madness. And as the works of Edgar Allen Poe and H.P. Lovecraft will attest, there's something about insanity that fascinates humans. I think this theme of Lear's madness resonates with readers to this very day.

The second reason for this scene's appeal is its drama. There's just so much going on in this scene compared to others. A massive storm blows while a mad King and his wise jester deliver soliloquies and prophecies. All of this insanity makes for a fascinating and visually striking image. The old adage "a picture's worth a thousand words" applies perfectly here. While the average reader may not remember that one scene where some guys plot about something, they will certainly remember that insane part where the old guy rips his clothes off and there's lots of thunder. I feel like this drama appeals to the audience on a visceral level. It's entertainingly dramatic theater at its finest.

This scene has been immortalized in art as an essential part of Shakespeare's canon. But why? Why would the image of an insane old man wandering in a storm become so popular? How does it still resonate with readers after 400 years?

I feel that the answer is twofold. First, the scene presents the character of Lear at his most miserable. The whole scene starts with Lear crying out to the sky "blow winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow" (Shakespeare III, ii). Right from the beginning the audience knows that Lear is feeling agitated. Lear carries on like this for the whole scene. He cries to the skies and moans of his wicked daughters. Through all of this the audience sees lear's sanity unfold before them and the king even admits "my wits begin to turn" (Shakespeare III, ii). Through all of this the audience gets a deep look into Lear's descent to madness. And as the works of Edgar Allen Poe and H.P. Lovecraft will attest, there's something about insanity that fascinates humans. I think this theme of Lear's madness resonates with readers to this very day.

The second reason for this scene's appeal is its drama. There's just so much going on in this scene compared to others. A massive storm blows while a mad King and his wise jester deliver soliloquies and prophecies. All of this insanity makes for a fascinating and visually striking image. The old adage "a picture's worth a thousand words" applies perfectly here. While the average reader may not remember that one scene where some guys plot about something, they will certainly remember that insane part where the old guy rips his clothes off and there's lots of thunder. I feel like this drama appeals to the audience on a visceral level. It's entertainingly dramatic theater at its finest.

Friday, April 1, 2016

Blog Post #33

You know, having only read the first couple scenes of King Lear, I feel kind of bad for the guy. He's old, dying, senile, and he has to deal with a couple crazy catty daughters. Let's start off with Goneril. When Lear asks Goneril to publicly declare how much she loves him, she proclaims "Sir, I love you more than words can wield the matter" (Shakespeare I. i). Now this may seem all well and good, she just loves her father a whole bunch. This whole monologue of professed love is a ruse however. Goneril couldn't care less about her father, she just wants some of the land he's giving away. So, we have a trusted daughter of nobility who is willing to lie and conspire to gain power. Sounds like a perfect recipe for some drama.

Regan is the middle child and it shows. When she is asked how much she loves her father the reply basically boils down to "Um, as much as my big sister... And then some!" This response shows that Regan struggles to live up to her older sister, Goneril. Regan's profession of love for her father is also just as hollow as Goneril's, as Kent and Cordelia would attest.

While Goneril and Regan share many character traits (Lying and scheming for starters), Cordelia stands alone. Lear's youngest daughter is also his favorite, he even proclaims "I loved her most" (Shakespeare I. i). Cordelia is fair and honest even when asked by her father for a public declaration of love. She's not going to lie to her father just to get some land (even if it's the finest portion). Cordelia's loyalty and love for her father is a sharp contrast to her conniving sisters.

To sum things up, Goneril and Regan are an axis of evil and Cordelia is the good daughter. Methinks things are going to get messy in ancient England...

While Goneril and Regan share many character traits (Lying and scheming for starters), Cordelia stands alone. Lear's youngest daughter is also his favorite, he even proclaims "I loved her most" (Shakespeare I. i). Cordelia is fair and honest even when asked by her father for a public declaration of love. She's not going to lie to her father just to get some land (even if it's the finest portion). Cordelia's loyalty and love for her father is a sharp contrast to her conniving sisters.

To sum things up, Goneril and Regan are an axis of evil and Cordelia is the good daughter. Methinks things are going to get messy in ancient England...

Friday, March 18, 2016

And isn't it ironic?

Irony is... tricky. There's several varieties of it and it's easy to get confused about what is and isn't irony. So, let's get some definitions going (for your sake and mine)

Dramatic Irony: Irony caused by readers knowing information that characters do not

Verbal Irony: A figure of speech (often sarcastic) that describes something opposite to how we normally would

Situational Irony: When readers are expecting one thing to happen, but a completely different thing does.

Act 2 scene 2 of Shakespeare's King Lear contains examples of all three forms of irony. Kent's ark in this scene is an example of situational irony. Kent, a man of the law fights with Oswald, a greedy schemer. In this case, one would expect Oswald to receive punishment for his deeds against the king; but Kent is the person who winds up in the stocks. This reversal of who sees the consequences for a crime is super ironic.

This scene also contains a nice example of verbal irony. When Kent's fate is being debated bby the various and sundry nobles, Cornwall refers to Kent as "You stubborn ancient knave, you reverent braggart" (Shakespeare II, ii 136). This is line is ironic for a couple reasons. First, Kent is old, but saying he is "ancient" is a huge overstatement by Cornwall. If Kent is "ancient" then his master Lear must predate the dinosaurs. Second, the two words of the phrase "reverent braggart" have polar opposite connotations. Someone who's reverent is very devoted; but a braggart is someone who endlessly boasts. In this line Cornwall uses a positive term (reverent) to describe how terrible he thinks Kent is. This reversal of connotation falls squarely into the camp of irony.

Cornwall's line also demonstrates the dramatic irony of scene two. He calls Kent a knave and treats him like one. None of the characters in the scene know that Kent is actually a nobleman in disguise. Thinking Kent a mere servant, all of the characters are willing to treat him as something lesser than them. But the good folks in the audience know that Kent is actually a knight and that he's doing the right thing by stopping Oswald.

This my dear friends, is truly dramatic irony.

All of this irony has major implications for the play's setting. The biggest of these is that the setting of King Lear is a place of endless reversals and confusion. Nothing is what is seems and everyone has their secrets that they hide. Another implication is that there's lots of corruption in Lear's kingdom. The criminals go free while the king's messenger sits in the stocks for goodness sake!

Wednesday, March 16, 2016

Is the fool a fool if he's a smart fool???

King Lear is full of character's in high places doing really dumb things. Take for instance, when King Lear exiles his favorite daughter and best knight on a whim. Or when said knight returns to serve his master in disguise, because loyalty? There's one character so far in the play that demonstrates much wisdom, and that is the Fool.

That's right, a character with no name other than his job description is the smartest guy in Lear's company. King Lear calls for the Fool seeking simple entertainment, but instead receives biting political commentary which he promptly disregards. In scene 4 the first thing the Fool does is give Kent/Caius his coxcomb (or hat). At first it's like, "Ho! What a silly jester!" because of the implication that Kent (a knight) is the actual fool. But when Kent asks the Fool why he offered the coxcomb the response is

Why? For taking one’s part that’s out of favor. Nay, an thou canst not smile as the wind sits, thou'lt catch cold shortly. There, take my coxcomb. Why, this fellow has banished two on ’s daughters, and did the third a blessing against his will. If thou follow him, thou must needs wear my coxcomb.—How now, nuncle? Would I had two coxcombs and two daughters. (Shakespeare 1, iv 102-109)

The Fool is basically telling Kent that he is true fool for following King Lear. Anyone who would serve a man who makes as many bad decisions as Lear is not a bright person. The Fool changed a simple joke about Kent's status into harsh commentary on the wisdom of anyone following King Lear. This line makes it obvious that although the Fool is a comedian, he is very aware of what his King has done and the all the faults he has.

The fool spends basically the rest of the scene mocking the king's status and decisions. He reminds Lear that he has nothing now that he's given the kingdom away. He calls the King a fool several times (and somehow doesn't get exiled like everyone else). He even says that Lear has "madest thy daughters thy mothers" (Shakespeare I, iv 176-177) in regards to the dividing of England. The fool seriously goes all out in reminding the King that he's a major idiot. The line "I am better than thou art now. I am a fool. Thou art nothing" (Shakespeare I, iv 198-199) is perhaps the Fool's most honest and damning.

All of the Fool's commentary and dialogue makes his true intelligence obvious. He's aware enough of the world around him to look past titles like "king" and "lady" to see the truth of things AND he's willing to express those truths to people in power. The fool can see that the people around him are truly the ones making foolish decision after foolish decision and he knows that he can stand above them. He honestly would make a better ruler than any of the "nobility" in this play.

In conclusion... #Fool4president2016!

Why? For taking one’s part that’s out of favor. Nay, an thou canst not smile as the wind sits, thou'lt catch cold shortly. There, take my coxcomb. Why, this fellow has banished two on ’s daughters, and did the third a blessing against his will. If thou follow him, thou must needs wear my coxcomb.—How now, nuncle? Would I had two coxcombs and two daughters. (Shakespeare 1, iv 102-109)

The Fool is basically telling Kent that he is true fool for following King Lear. Anyone who would serve a man who makes as many bad decisions as Lear is not a bright person. The Fool changed a simple joke about Kent's status into harsh commentary on the wisdom of anyone following King Lear. This line makes it obvious that although the Fool is a comedian, he is very aware of what his King has done and the all the faults he has.

The fool spends basically the rest of the scene mocking the king's status and decisions. He reminds Lear that he has nothing now that he's given the kingdom away. He calls the King a fool several times (and somehow doesn't get exiled like everyone else). He even says that Lear has "madest thy daughters thy mothers" (Shakespeare I, iv 176-177) in regards to the dividing of England. The fool seriously goes all out in reminding the King that he's a major idiot. The line "I am better than thou art now. I am a fool. Thou art nothing" (Shakespeare I, iv 198-199) is perhaps the Fool's most honest and damning.

All of the Fool's commentary and dialogue makes his true intelligence obvious. He's aware enough of the world around him to look past titles like "king" and "lady" to see the truth of things AND he's willing to express those truths to people in power. The fool can see that the people around him are truly the ones making foolish decision after foolish decision and he knows that he can stand above them. He honestly would make a better ruler than any of the "nobility" in this play.

In conclusion... #Fool4president2016!

Tuesday, March 8, 2016

Good Ol' Edmund!

In the play King Lear, the character edmund is a conniving son of a gun. In act 1, scene 1, Edmund says only three lines. However, every single one of them present a persona of the ideal, subserviant son. He always uses the the phrases "my lord" and "sir" to indicate his (feigned) respect for the nobility surrounding him.

In scene 2, Shakespeare gives Edmund time to soliloquize and his true feelings are revealed. Edmund first expresses contempt and jealously for his brother Edgar, who is the legitimate son of Gloucester.

In scene 2, Shakespeare gives Edmund time to soliloquize and his true feelings are revealed. Edmund first expresses contempt and jealously for his brother Edgar, who is the legitimate son of Gloucester.

As to the legitimate.—Fine word, “legitimate”!—

Well, my legitimate, if this letter speed

And my invention thrive, Edmund the base

Shall top th' legitimate. I grow, I prosper.

Now, gods, stand up for bastards! (Shakespeare I, ii 19-24)

Edmund feels such jealousy for his half brother that he hatches a plot to steal his lands and inheritance. So, Edmund does what any good brother would do and tries to convince his father that Edgar is out for his blood to speed up the inheritance process. Edmund is just as much of an evil schemer as King Lear's eldest daughters, with the addition of a huge inferiority complex towards his legitimate brother.

You could say Edmund is a real................

Bastard!

(mad applause and laughter)

That's all folks! I'll be here all week!

Wednesday, February 24, 2016

King Lear Prediction

"... the theme of King Lear may be stated in psychological as well as biological terms. So put, it is the destructive, the ultimately suicidal character of unregulated passion, its power to carry human nature back to chaos."-- Harold C. Goddard (1951)

Based off of this quote I get a strong feeling that the play King Lear features a tragic hero who makes a terrible mistake. My guess is that the hero's tragic flaw involves unbridled passion which leads to his (and possibly a kingdom's) downfall. I also get an impression that this play will feature some focus on human nature, otherwise I don't think that this quote would focus on passion's power "to carry human nature back to chaos". To be honest, I'm actually kind of pumped to read King Lear. If it's anywhere near as engaging as Antigone was, then I know I'll have a good time learning about some classic literature!

Based off of this quote I get a strong feeling that the play King Lear features a tragic hero who makes a terrible mistake. My guess is that the hero's tragic flaw involves unbridled passion which leads to his (and possibly a kingdom's) downfall. I also get an impression that this play will feature some focus on human nature, otherwise I don't think that this quote would focus on passion's power "to carry human nature back to chaos". To be honest, I'm actually kind of pumped to read King Lear. If it's anywhere near as engaging as Antigone was, then I know I'll have a good time learning about some classic literature!

Monday, February 22, 2016

My Response to "The Collar" by George Herbert

Gee whiz! This poem sure is a doozy...

To start with, this poem is dense. If readers don't pay close attention to the poem's imagery and structure, they are going to get lost. Like, "I was trying to go to get a burger but now I'm in Cuba" lost. This poem takes on the structure of a man's howl against God, the world, and basically everything. All the material between the quotation marks (lines 1-32) is the speaker's dialog; after 30-some lines however, its easy to lose track of that fact and the poem's meaning with it. Without the realization that most of the poem is dialog, it just seems like a lot of random images and questions. But, with an understanding of the poem's structure we start to see its theme emerge. In the 4th line the speaker says "My life and lines are free, free as the road". This is obviously the speaker proclaiming his freedom from something; but what is it that's oppressing him? The answer comes in the last lines; "But as I raved... methought I heard one calling, child! And I replied My Lord". This poem shows someone railing against God (or some higher power) but then realizing they ultimately are subservient to said force.

Now that we've gotten the analysis of the poem itself out of the way, let's talk meaning! One way I could see this poem is as a getting upset and going on a long rant, only to realize that he's wrong. Imagine a teenager, but on artistic steroids. Instead of spewing regular complaints, he spits out metaphors and great lamentations! In this reading of the poem "God" is simply a representation of the speaker's better senses and the whole piece is a great work of humanism. It shows humankind conquering its own whiny pretentiousness. It's a very roundabout and symbolic way of showing this idea however, which leads me to believe that the poem is more spiritual in nature.

A core tenant of the Christian faith is that God loves everyone on Earth and see's them as his "children". Throughout this poem I contend that the speaker acts extremely childish. The very first thing to happen is the speaker hitting an inanimate object in anger, just like a toddler. They then proceed to "cry" about all of their grievances until, finally, the parent (God in this case) says "Child!". And like magic, they stop and go "mommy!" (or daddy). This interpretation of the poem presents God as a parent who loves his children, yet still commands their respect. He's the lovable father that nurtures his child while still instilling morals and ideals within them. The big idea here is that mankind is an obedient child; although we may sometimes raise our voices in rebellion, there is nothing but reverence when our father speaks. What makes this whole relationship possible is love and respect between a creator and its progeny.

Part of the beauty of this poem--and metaphysical poetry in general--is that through all the complex metaphors, structures, and images readers can see many possible interpretations. And even if our interpretations vary, both can still contain some kernel of truth. So, while this poem isn't really the most emotionally compelling, it certainly has a ton of intellectual depth packed into its lines.

To start with, this poem is dense. If readers don't pay close attention to the poem's imagery and structure, they are going to get lost. Like, "I was trying to go to get a burger but now I'm in Cuba" lost. This poem takes on the structure of a man's howl against God, the world, and basically everything. All the material between the quotation marks (lines 1-32) is the speaker's dialog; after 30-some lines however, its easy to lose track of that fact and the poem's meaning with it. Without the realization that most of the poem is dialog, it just seems like a lot of random images and questions. But, with an understanding of the poem's structure we start to see its theme emerge. In the 4th line the speaker says "My life and lines are free, free as the road". This is obviously the speaker proclaiming his freedom from something; but what is it that's oppressing him? The answer comes in the last lines; "But as I raved... methought I heard one calling, child! And I replied My Lord". This poem shows someone railing against God (or some higher power) but then realizing they ultimately are subservient to said force.

Now that we've gotten the analysis of the poem itself out of the way, let's talk meaning! One way I could see this poem is as a getting upset and going on a long rant, only to realize that he's wrong. Imagine a teenager, but on artistic steroids. Instead of spewing regular complaints, he spits out metaphors and great lamentations! In this reading of the poem "God" is simply a representation of the speaker's better senses and the whole piece is a great work of humanism. It shows humankind conquering its own whiny pretentiousness. It's a very roundabout and symbolic way of showing this idea however, which leads me to believe that the poem is more spiritual in nature.

A core tenant of the Christian faith is that God loves everyone on Earth and see's them as his "children". Throughout this poem I contend that the speaker acts extremely childish. The very first thing to happen is the speaker hitting an inanimate object in anger, just like a toddler. They then proceed to "cry" about all of their grievances until, finally, the parent (God in this case) says "Child!". And like magic, they stop and go "mommy!" (or daddy). This interpretation of the poem presents God as a parent who loves his children, yet still commands their respect. He's the lovable father that nurtures his child while still instilling morals and ideals within them. The big idea here is that mankind is an obedient child; although we may sometimes raise our voices in rebellion, there is nothing but reverence when our father speaks. What makes this whole relationship possible is love and respect between a creator and its progeny.

Part of the beauty of this poem--and metaphysical poetry in general--is that through all the complex metaphors, structures, and images readers can see many possible interpretations. And even if our interpretations vary, both can still contain some kernel of truth. So, while this poem isn't really the most emotionally compelling, it certainly has a ton of intellectual depth packed into its lines.

Critical Lens Reflection.

https://docs.google.com/a/jeffcoschools.us/document/d/1gj9Flpauow1WCJyJi_s6nOyOP6f15mlYkCy1rZLsoTQ/edit?usp=sharing

Whew, now THAT was an essay. The process of composing this essay felt very... stimulating? Yeah, that's how it was. Every single step of the way offered a new challenge to me. From finding sources, to extracting quotes, and finally writing the thing; I constantly came into roadblocks that required me to really flex the ol' cranium. How do I find relevant materials? Is this analysis deep enough? How can I make this intro pop? I found the answers to most of these even if my first draft felt a bit half-baked.

Now revising was the surprising part. I thought "oh I'll expand on some stuff and then this here essay will be swell!". I couldn't have been more wrong. It took a whole lot of thinking to find changes that expanded on what I wrote while maintaining consistency with what already existed. But I got through it with the help of some coffee and some jazz. (shout out to the Robert Glasper trio!)

Overall, I'm actually pretty proud of my essay. Although I wouldn't jump up to write another critical lens essay, I'm glad that I got some experience in the style. Have a most chill day folks!

Whew, now THAT was an essay. The process of composing this essay felt very... stimulating? Yeah, that's how it was. Every single step of the way offered a new challenge to me. From finding sources, to extracting quotes, and finally writing the thing; I constantly came into roadblocks that required me to really flex the ol' cranium. How do I find relevant materials? Is this analysis deep enough? How can I make this intro pop? I found the answers to most of these even if my first draft felt a bit half-baked.

Now revising was the surprising part. I thought "oh I'll expand on some stuff and then this here essay will be swell!". I couldn't have been more wrong. It took a whole lot of thinking to find changes that expanded on what I wrote while maintaining consistency with what already existed. But I got through it with the help of some coffee and some jazz. (shout out to the Robert Glasper trio!)

Overall, I'm actually pretty proud of my essay. Although I wouldn't jump up to write another critical lens essay, I'm glad that I got some experience in the style. Have a most chill day folks!

Friday, February 12, 2016

The (kind of tragic) Dead Poet's Society

After watching The Dead Poet's Society (and eating an ungodly amount of Cheetos) I have come to the conclusion that the film is not a true Greek Tragedy, but an evolution of the form. "What?!" You may be thinking, "No way, Greek tragedy is like an ancient style that's like, really stagnant". But I say nay! The Dead Poet's Society represents a totally tubular advance in the conventional Greek format.

But first, let's go over what parts of the film ARE definitely classic tragedy. Right of the bat we have Neil Perry, a good old fashioned hero. He was born into a noble bloodline; anyone attending the Welton academy has parents who can afford to send their sons to boarding school. He has a tragic flaw in the way he thinks the only way he can live is by acting and not having the strength to resist his father's wishes. And (most importantly) he suffers a huge downfall, he kills himself on a cold winters night. Was it the will of the Gods? Hubris? Fate? I'm personally on the fate side. As a "romantic" Neil was destined to die a death in the name of love (of acting).

This movie also runs parallel to Greek Tragedy in a few other ways. The film contains several "odes" in the form of Mr. Keating's impassioned lessons to his pupils. Mr. Keating acts as the Choragos in this tragedy by being a leader to the students (who are the chorus). In the end of the film when the students stand to say farewell to their beloved teacher it almost seems like a classical exodus chanted by the chorus.

Now, I contend that The Dead Poet's Society is not a true tragedy for one major reason, the characterization of the chorus. In Greek tragedy the chorus is a mildly unsettling group of people in masks who walk across the stage while chanting odes and poetry; the individual members have no strong or distinct personality of their own. In TDPS however, every boy in the chorus has their own unique character and I would contend that some of them are tragic heroes in their own right. Take Charlie Dalton for instance. He is of the same noble bloodline as the other students, has the tragic flaw of hubris, makes major mistakes in publishing an article in the paper and punching another student, undergoes a major change by assuming the name "Nuwanda", and ultimately has the downfall of being expelled. In a classic Greek tragedy, a member of the chorus would never get such a complete character ark. A true Greek tragedy would never have such development of minor characters! In fact, at times it seemed like our "tragic hero" Neil Perry wasn't even the film's main focus.

On a side note, I'm glad that this film breaks the tragic mold. I think that Greek tragedy is a really kind of restrictive form. I mean, having more than two characters onstage at once was considered crazy innovative in those times! And don't even get me started on those masks... (shudder)

Monday, February 8, 2016

Everybody Hurts (In a constructive way through the viewing of tragedy)

Imagine the following... You just woke up this morning and you're feeling deathly ill. On a normal day you might have stayed home, but this morning you have an important test in your 1st hour super-omega difficult calculus class. After a cold cup of coffee and slice of un-toasted bread, (Surprise! your electricity is out!) you drag yourself out to your car (which is covered in ice, this being a tragedy and all). After getting the keys in the ignition, you hear a sound vaguely reminiscent of third grade recorder class combined with the moans of agony a tortured hostage might give; and your car fails to start. Now, you are desperately running through the snow to get to your school; which is 7 miles away (you choice enrolled after all). All of your efforts have been in vain however, the bell rang just a few minutes ago and the teacher locked their door wondering why their usual super-student isn't in attendance for the huge test. So, you take the long, dejected walk home--at least you may find some comfort there. But as you open the front door a distinct aura of death overcomes you and in the adorable bed you bought him just last week lies your now deceased puppy, Spot.

Take a deep breath...

Aren't you glad that isn't how your morning went?

This is the core of tragedy. Through viewing the suffering of others we can feel fear and pity for them. Fear that we may ourselves one day face a horrible tragedy similar to the one on stage, and pity for the hero's downfall. According to Aristotle these to responses can evoke a state known as catharsis. Catharsis is like an emotional deep cleanse through an outburst of negative feelings. By getting out all of the fear and sadness, we can feel a state of emotional ease and purity. Some people find catharsis through screaming at walls and listening to angry music. But I believe that truly sophisticated AP Lit loving individuals can find it through a good tragedy. (the info for this paragraph comes from David E. Riva's TEDEd video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVRU5MVYNiw)

There is another, more scientifically proven way that tragedy affects the human psyche. Remember in the first paragraph how I described your dead puppy Spot? That lifeless, literary corpse of a dog most likely brought images of a real life pet to your mind. Wouldn't it truly be a tragedy if a beloved pet suddenly died? In 2012 The Ohio State university conducted a study to figure out why tragedy makes us tick. They found that after people watched a sad movie that featured two lovers dying in a war, they often recorded thinking about their own relationships. Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick of The Ohio State university says “People seem to use tragedies as a way to reflect on the important relationships in their own life, to count their blessings,”.

Sadness and heartache a part of the human experience. Everyone has had friends they've lost, tests they've failed, and actions they regret. I think that the reason we are drawn to tragedy is that it gives us a safe way to work out those feelings AND helps us feel grateful for the good things in life.

There is another, more scientifically proven way that tragedy affects the human psyche. Remember in the first paragraph how I described your dead puppy Spot? That lifeless, literary corpse of a dog most likely brought images of a real life pet to your mind. Wouldn't it truly be a tragedy if a beloved pet suddenly died? In 2012 The Ohio State university conducted a study to figure out why tragedy makes us tick. They found that after people watched a sad movie that featured two lovers dying in a war, they often recorded thinking about their own relationships. Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick of The Ohio State university says “People seem to use tragedies as a way to reflect on the important relationships in their own life, to count their blessings,”.

Sadness and heartache a part of the human experience. Everyone has had friends they've lost, tests they've failed, and actions they regret. I think that the reason we are drawn to tragedy is that it gives us a safe way to work out those feelings AND helps us feel grateful for the good things in life.

Tuesday, February 2, 2016

Critical Lens Reflection

Let me tell you, I'm thankful that I likely won't ever have to write a literature critical analysis ever again. From finding research materials, to extracting information, and finally coming up with analysis; the whole project felt insurmountable. Once I finally just sat down and started writing, the process got a bit easier. But, towards the end of my essay I just started running out of things to say and the whole affair feels a bit under-cooked. There was one redeeming part of this assignment however as I found great entertainment in reading accounts of F. Scott Fitzgerald being a lying jerk sometimes. Also, this Matthew J. Bruccoli guy seems weirdly obsessed with Fitzgerald's life; it's just kind of creepy how much the man has written on the topic. My favorite quote from Bruccoli (in regards to Zelda Fitzgerald's lone novel) is "Save Me the Waltz is worth reading partly because anything that illuminates the career of F. Scott Fitzgerald is worth reading" (southern literary journal). I also found all of Bruccoli's occasional judgments of the Fitzgerald's marriage (in his epic 600 page biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald) to be fairly amusing.

Friday, January 29, 2016

A close reading of the Parados from Antigone

1. Dirce was a Naiad who was married to king Lykos of Thebes. She was cruel to her niece Antiope however, and as a result she was tied to a wild bull and killed. Since she was a dedicated follower of Dionysus he made a stream flow for her near Thebes. The significance of armies fighting by the waters is that they are near a place where the nymph's loyalty was rewarded. Just as their loyalty to--or against Thebes shall have consequence.

2. "Windy phrases" means that Polyneices used lofty words of glory to rouse his troops.

3. A metaphor in the Parados is "He the wild eagle screaming insults above our land" (lines 94-95). A simile from the passage is "Rose like a dragon behind him" (line 104).

4. The pronouns "them" and "their" in this passage refer to the participants in the battle.

5. A couple examples of personification from this text are "The Earth struck him" and "O marching light."

6. I think "he" in line 100 refers to Polyneices, but I'm not 100% sure.

7. When we hear the word "bray" in line 106 we are supposed to think of horses that Sophocles implies the men resemble.

8. The word "he" in lines 107-110 refers to the gods looking down on the battle.

9. Lines 119-122 tell of the demise of the two opposing brothers in a long raging duel.

10. I don't think that line 124 can be called personification because it refers more to the residents of Thebes than the city itself.

2. "Windy phrases" means that Polyneices used lofty words of glory to rouse his troops.

3. A metaphor in the Parados is "He the wild eagle screaming insults above our land" (lines 94-95). A simile from the passage is "Rose like a dragon behind him" (line 104).

4. The pronouns "them" and "their" in this passage refer to the participants in the battle.

5. A couple examples of personification from this text are "The Earth struck him" and "O marching light."

6. I think "he" in line 100 refers to Polyneices, but I'm not 100% sure.

7. When we hear the word "bray" in line 106 we are supposed to think of horses that Sophocles implies the men resemble.

8. The word "he" in lines 107-110 refers to the gods looking down on the battle.

9. Lines 119-122 tell of the demise of the two opposing brothers in a long raging duel.

10. I don't think that line 124 can be called personification because it refers more to the residents of Thebes than the city itself.

Monday, January 25, 2016

Read Along of mentor text #3

- Right off the bat I notice the MLA formatting, this makes it very obvious that I'm reading an academic essay.

- The title follows a similar format to the previous mentor texts (entertaining bit!: a ____ perspective of ___)

- The opening paragraph makes an argument as to why the formalist lens is the best way of analyzing Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

- The first paragraph contains the thesis. (Surprise!)

- The second paragraph defines a frame narrative for readers AND explains its significance to the text.

- The text then shifts gears in the third paragraph to analysis of the character Marlow.

- The text then connects Marlow to the framing narrative.

- Wow, this text actually has a decent and (kind-of) fleshed out conclusion.

- Since this is a formalist essay, the only text mentioned in the works cited is the novella.

- The title follows a similar format to the previous mentor texts (entertaining bit!: a ____ perspective of ___)

- The opening paragraph makes an argument as to why the formalist lens is the best way of analyzing Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

- The first paragraph contains the thesis. (Surprise!)

- The second paragraph defines a frame narrative for readers AND explains its significance to the text.

- The text then shifts gears in the third paragraph to analysis of the character Marlow.

- The text then connects Marlow to the framing narrative.

- Wow, this text actually has a decent and (kind-of) fleshed out conclusion.

- Since this is a formalist essay, the only text mentioned in the works cited is the novella.

Monday, January 18, 2016

Sometimes, Ignorance is Bliss!

Walt Whitman has an interesting perspective on knowledge and beauty in his poem "When I Heard the Learn'd Astronomer". In the poem, the narrator describes how he walks out on a brilliant astronomer's lecture on the science of cosmos because he simply wishes to see the beauty of the night sky. Now I have to agree with Whitman's message that you don't necessarily need to understand something to see the beauty in it. For instance, would you rather look at this on a romantic date?

|

| By Michael J. Bennett (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

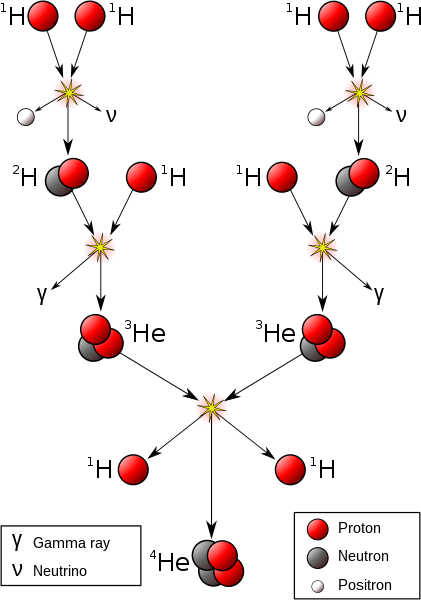

OR, would you prefer to see this image of the material stars are made of?

|

| By Borb [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

So while I mostly agree with the poem, I feel that Whitman's perspective of beauty over knowledge to be a bit one sided. Let's take a look at Chopin's Nocturne op. 9 no. 2 which can be found at the following link. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YGRO05WcNDk) I loved this song long before I even knew what on Earth a nocturne was. And I'm sure that any of my readers can see a similar haunting melancholy in the composition. However, the effect of the piece can be further amplified by knowledge of the sad life that Frederic Chopin lived. He was a romantic in exile from his native Poland, suffering from chronic illness and financial strife. Knowing the story of Chopin's life allows listeners to hear his music as a window into his struggles. It elevates the piece to a new level of emotion, one of empathy for the creator.

So... That's my first blog post. Thanks for reading, and have a wicked good rest of your day!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)